Verifying conditions on the ground against codes or standards is a key component of voluntary market-based tools such as certification. Typically, a team of auditors or other verification personnel visit locations and assess in how far companies or producers comply with a set of requirements. Those may be from a voluntary sustainability standard (VSS), government scheme or private sector scheme.

Labour standards are no exception. As many VSS have evolved in their understanding and inclusion of labour issues, and others have developed to focus on improving labour rights and conditions in workplaces around the world, so too has the work of auditors needed to evolve to ensure that labour practices are observed accurately, that non-compliances affecting workers are detected, and that effective plans for mitigating any labour issues are developed and implemented.

Labour auditing has, however, come under severe criticism. This often targets auditors used by retailers and manufacturers for their own private sector schemes, but VSS have also been implicated. The criticism includes concerns with the practical limitations of auditing such as time and resources available to spend in interviews and inspections, and arguments for stronger regulatory oversight. The strongest critics claim that auditing is being used to obfuscate or even encourage labour rights abuses and keep the focus on verification of compliance and not mitigation of actual harm.

ISEAL commissioned Proforest to review recent academic and civil society research to analyse findings from empirical studies on the effectiveness of labour auditing and recommendations to improve practice. Proforest’s review looked at 39 studies published between 2013 and 2023 that gathered data on labour auditing, with some of the original data going back to the early 2000s. Collectively, the studies provide evidence from more than 1,500 interviews with workers, auditors, employers, supply-chain actors and VSS staff; and statistical analysis of over 100,000 audit reports.

The 39 empirical studies covered three main sectors – agriculture and forestry, garments and textiles, and seafood and aquaculture – and help us to understand in greater depth what some of the challenges in labour auditing can be.

In 17 of the studies, some form of audit deception was reported, where employers might conceal information or coach workers on what to say to auditors. Around three quarters of the studies discussed limitations in auditing methodology, including auditors finding it difficult to uncover certain labour issues such as forced labour or discrimination. Since most of the studies included qualitative research, they give insights into the personal attitudes that affect audits, such as auditors finding it difficult to interpret indicators of a standard, or factory owners resenting being asked by buyers to comply with external certification audits. Half of the studies interviewed or surveyed workers, and as well as providing upsetting testimony of exploitative labour practices in the workplace, the research highlights that workers are often poorly informed about and excluded from visits by labour auditors.

A few cross-cutting themes that emerged from our review of evidence:

- There is ambiguity and overlap between VSS audits and audits conducted against buyers’ own standards. This affects the research itself, where it is often not clear if findings relate to a VSS or buyer’s scheme, which can be very different from one another in terms of auditing process, transparency, commercial pressures and so on. But the research shows that producers and employers also experience a sense of blurring between multiple schemes that they might choose or be required to participate in, leading to cynicism and audit fatigue.

- There are key differences between sectors that must be better understood if we are to improve detection and mitigation of labour issues. These differences relate to the nature of supply chains, commercial leverage of suppliers, and the geographies and practicalities of production. The review found that audit deception is particularly common in garment factories, for example. Agriculture presents challenges for auditors in identifying and reaching workers employed by smallholders. In fisheries, audit teams must find ways to interview workers in confidence away from employers’ oversight and to cover the multi-lingual nature of many fishing workplaces.

- The research lays bare many of the practical limitations of auditing as a verification tool. Some of these limitations can be addressed, for example by interviewing workers off-site or increasing sample sizes. But others are perhaps inherent to the auditing model. An audit will always be limited in duration (usually taking 3–5 days, sometimes less) and oriented towards checking compliance. Important discussions are already taking place within and beyond the ISEAL community on what improvements can be made – and how they should be funded – and where additional tools might be needed to monitor conditions year-round and to identify the root causes of labour issues.

- But when we assess the effectiveness of auditing and how it could be improved, it is also critical to consider the supply-chain context. What financial pressures are producers experiencing? What are the layers of production sub-contracting that can fog up the transparency of labour supply chains? The research shows how important the local political economy is – strong trade unions, well-resourced labour inspectorates and healthy labour market can all make it easier for auditors to detect and mitigate labour issues.

- There is growing awareness of gender, both in terms of how a worker’s gender affects the kinds of labour rights abuses they can experience, and in terms of how audits should be carried out. The research provide evidence that audit teams tend to record more labour non-compliances when there is at least one woman on the team and when auditors have received gender training.

- The studies raise important points for the bodies that oversee VSS standards. Several of the studies found that the wording of standards was too open to interpretation and that the evidence threshold are set so high that many likely violations of labour standards were going unrecorded by auditors. Yet although 31 of the studies discussed VSS audits, only nine of the studies included interviews with VSS staff. To an extent, researchers and NGOs have focused on speaking to workers, auditors and companies. VSS could be more involved in the conversation, and researchers could improve their understanding of how VSS and the various models of certification and verification work.

- We need better methods for assessing audit effectiveness. While the studies present us with comprehensive evidence that labour auditing is subject to flaws, they are not able to suggest with any degree of accuracy how widespread these documented limitations are. Only a few of the studies capture how the quality and effectiveness of labour audits has changed over time. We also need more analysis of how the auditing process contributes to continuous improvement among producers and employers. This aspect was under-researched in the studies.

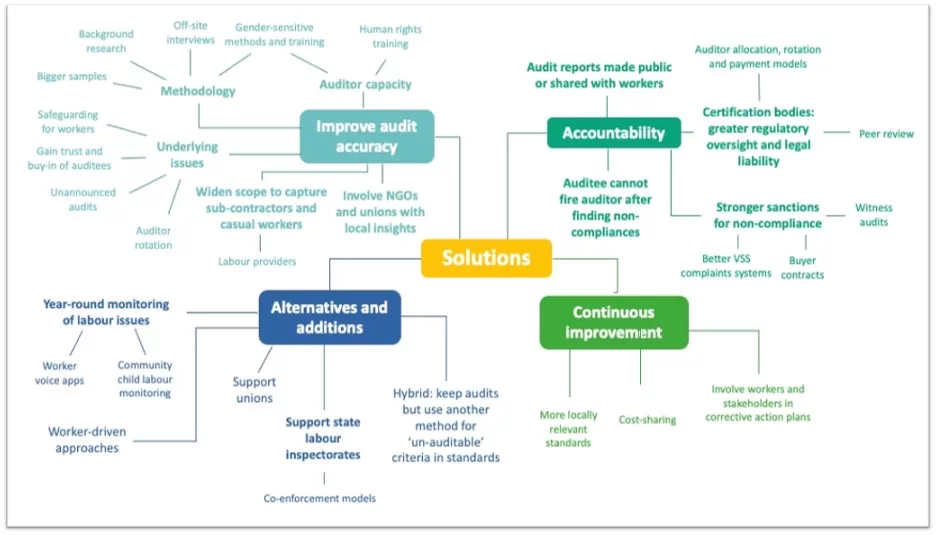

- There is lively and productive work going on to address some of the challenges that the research studies, and the public critiques, have raised. A wide range of solutions are being discussed and put into place. Among them: awareness-raising to empower workers; better training for auditors; legal and contractual changes to make producers and certification bodies more accountable; greater involvement of communities and civil society; technological solutions such as a worker voice apps; shared responsibility to help producers shoulder the financial cost of compliance; and hybrid solutions to complement auditing with other tools. Indeed, several of these have already been implemented by some VSS, which is not yet reflected in the academic research, so a future analysis of the effect of these measures would be extremely valuable.

In the report we grouped the recommendations into 4 main categories, as reflected in figure 1:

- Recommendations to improve audit accuracy

- Recommendations for greater accountability

- Promoting continuous improvement

- Alternatives and additions to auditing

Figure 1- Summary graphic of recommendations from the literature to improve labour auditing

Overall, we need to discuss what the purpose of auditing is in the context of sustainability standards – and what it can and cannot achieve. That being said, there is clear scope for improvements to current audit practices to increase effectiveness in detecting labour rights abuses and playing a role in identifying and remedying them.