It has been a bad few years for the world’s tropical forests. Last year, annual records for the loss of primary tropical forest – often thought of as pristine forest – were smashed. In total, 6.7 million hectares were lost at a rate of 18 football pitches per minute. This was terrible news for both the climate and nature, with tropical forests being vital for storing carbon and providing a home to the greatest diversity of plants and animals on land. It is also deeply concerning for the livelihoods and cultures of a billion people who live in or near forests.

Yet despite this rampant loss, over a billion hectares of primary tropical forest – and two thirds of tropical forests in total – still remain. In addition, some major tropical forest countries have achieved remarkable reductions in deforestation in recent decades. For example, Brazil reduced deforestation in the Amazon rainforest by 84% between 2004 and 2012, and Indonesia reduced deforestation by 78% between 2016 and 2021. Why is so much tropical forest still standing despite the relentless expansion of agriculture and demand for minerals and timber? And how did Brazil and Indonesia reduce deforestation by so much?

How we identified what keeps forests standing

We already know lots about the effects of specific policies on reducing deforestation because they are usually implemented in clearly defined areas and timeframes. This makes their impacts (relatively) straightforward to measure. Increasingly, researchers have also been evaluating the impacts of less clearly defined factors like governance. But deforestation is a very complex phenomenon. For forests to be conserved, specific mixes of different policies and factors are needed at specific times in specific places. Some of these factors – especially political and economic factors – are difficult to measure or even define. Still, if we could identify all the factors that have contributed to protecting forests where they remain, that could go a long way towards telling us how to keep forests standing in the long term.

To identify the full range of factors that have protected forests in the Brazilian Amazon and Indonesia we turned to 36 experts, most of whom were from one of the two countries. Working with experts can produce less reliable information than carefully controlled scientific experiments because there is a risk that social interactions influence their judgements. For example, particularly charismatic individuals could unduly sway the opinions of others. Or wanting to get along could lead a group of experts to make incorrect judgements just to minimise conflict. But if these problems are managed carefully, expert opinion can provide insights about subjects that are otherwise difficult to assess. We achieved this balance using the Delphi method: a series of surveys where the results are repeatedly shared with participants, but their identities are kept secret. By keeping experts anonymous, the Delphi method allows them to converge on more accurate judgements while avoiding the pitfalls of social interaction.

What factors protected forests in Brazil and Indonesia?

Our experts perceived some differences between the two countries. In the Brazilian Amazon, where there has been a history of strong public interventions to conserve forests, they emphasised actions by the government. These included the Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (Portuguese acronym PPCDAm). In Indonesia, meanwhile, experts flagged a mix of actions by the public and private sectors as well as civil society. These included policies by companies to remove deforestation from supply chains and the Indonesian government’s moratorium on new logging licences. The experts’ judgements in Indonesia reflected the relatively more prominent role of the private sector and civil society compared to Brazil, although the government was still seen as important.

But in both countries, our experts were absolutely clear that law enforcement and political will and leadership were by far the most important factors for protecting forests. Other factors that often feature less frequently in studies on deforestation control, including advocacy by civil society organisations but also public awareness and international diplomacy, were also perceived to be important.

The importance of different factors changed over time

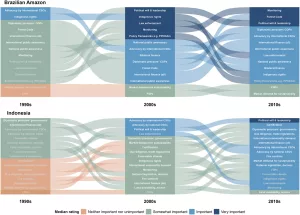

Based on prompts by our experts, we decided to investigate further about how these factors’ importance varied over time (Figure – click on the figure to zoom in). This is where things got really interesting. While political will and law enforcement were clearly important in the periods where deforestation was reduced the most, they were preceded by advocacy by national and international civil society organisations, international diplomacy (including pressure by other governments, UN climate conferences, and international finance), and public awareness. In Brazil, the recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples and their lands also played an important role.

Figure: Changes in the perceived importance of different factors over time. Reproduced from Lyons-White, Spencer, et al. (2025) Conservation Letters 18(4):e13120

Political will doesn’t come from nowhere

This trajectory of the importance of different factors tells us two things. First, political will and leadership – and the law enforcement that flows from them – are the most important factors for protecting forests. But

second, the conditions under which political will to protect forests emerges are created by long-term, sustained pressure from civil society organisations, the public, and the international community. While the latest conservation schemes and policies might seem attractive, and the urgency of deforestation demands immediate results, it is these long-term, slow-burn, sustained actions that keep forests standing.

What needs to happen now

This core message from our research comes at a crucial time. Around the world, political will to protect the environment is being challenged. In the past few months, multiple banks have withdrawn from the Net Zero Banking Alliance following the collapse of political will to tackle climate change in the US government. The forest conservation movement is not immune: in Indonesia, political will on forest protection appears to be changing, while the EU Parliament passed an objection to the EU Deforestation Regulation’s country benchmarking system that threatens to undermine the regulation’s stringency. Against this backdrop of turbulence for the global environmental movement, our findings have important practical implications for colleagues working to conserve tropical forests.

Civil society advocates must continue raising public awareness both domestically and internationally to drive political will, and their backers should invest for the long game. International diplomacy also has a crucial role to play, and the forthcoming climate conference in the Amazon is a unique opportunity to recharge international partnership on this agenda, after two years of fractious debates on the EU deforestation regulation.

For policymakers in tropical forest countries, demonstrating leadership on current laws and agreements is vital. This often requires resources to be focussed on the enforcement or delivery of existing good policy and programmes rather than developing entirely new ones.

For companies, our findings from Indonesia make compelling reading. Business commitments to sustainable palm oil reinforced strong political leadership in the 2010’s and contributed to steep reductions of deforestation by 2020. There is also good evidence from both countries that the best value chain and landscape approaches can contribute to lower deforestation irrespective of the levels of political will at national level.

As delegations from around the world converge on the Brazilian Amazon city of Belém in November for the 30th UN climate conference, governments, companies, and civil society organisations need to rebuild momentum for increased forest protection. We still have a billion hectares of tropical forests left. Let’s learn from our past successes to keep it that way.